A Synthetic Building Operation Dataset

This is the official repository prepared for a dataset descriptor - A Synthetic Building Operation Dataset published in Scientific Data journal.

Li, H., Wang, Z. & Hong, T. A synthetic building operation dataset. Sci Data 8, 213 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00989-6

It contains:

- A brief introduction to the dataset.

- A Jupyter notebook with Python script to extract and visualize the data.

- A step-by-step guidance to generate synthetic building operation data.

- A discussion of example use cases of the dataset.

About the dataset:

This is a synthetic building operation dataset which includes HVAC, lighting, miscellaneous electric loads (MELs) system operating conditions, occupant counts, environmental parameters, end-use and whole-building energy consumptions at 10-minute intervals. The data is created with 1395 annual simulations using the U.S. DOE detailed medium-sized reference office building, and 30 years’ historical weather data in three typical climates including Miami, San Francisco, and Chicago. Three energy efficiency levels of the building and systems are considered. Assumptions regarding occupant movements, occupants’ diverse temperature preferences, lighting, and MELs are adopted to reflect realistic building operations. A semantic building metadata schema - BRICK, is used to store the building metadata. The dataset is saved in a 1.2 TB of compressed HDF5 file. This dataset can be used in various applications, including building energy and load shape benchmarking, energy model calibration, evaluation of occupant and weather variability and their influences on building performance, algorithm development and testing for thermal and energy load prediction, model predictive control, policy development for reinforcement learning based building controls.

Access the Dataset

Option 1 - Direct Download

The dataset is registered with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Open Energy Data Initiative (OEDI) and is stored with Amazon Simple Storage Service (S3). More details about the service can be found at this site. To download the dataset, first make sure the AWS Command Line Interface (CLI) is installed. Then, make sure you have enough (>1.2TB) disk space, and run the command below to download the file to the <local_directory>.

aws s3 cp s3://oedi-data-lake/building_synthetic_dataset/A_Synthetic_Building_Operation_Dataset.h5 <local_directory> --no-sign-request

Option 2 - Access Subset from S3

Downloading the 1.2TB HDF5 file in one piece requires large disk space and can be time-consuming. Alternatively, you can access the data by subset directly from the AWS S3 bucket, which is enabled by the hierarchical structure of the HDF5 file. The code snippet for this purpose is:

# Import dependencies

import s3fs

import h5py

# Access the file from S3 bucket

dir_aws_s3 = 's3://oedi-data-lake/building_synthetic_dataset/A_Synthetic_Building_Operation_Dataset.h5'

s3 = s3fs.S3FileSystem()

hdf = h5py.File(s3.open(dir_aws_s3, "rb"))

The Jupyter notebook provides a full example. You might need to follow the instruction to configure AWS command line credentials to read from S3.

Data Extraction and Visualization:

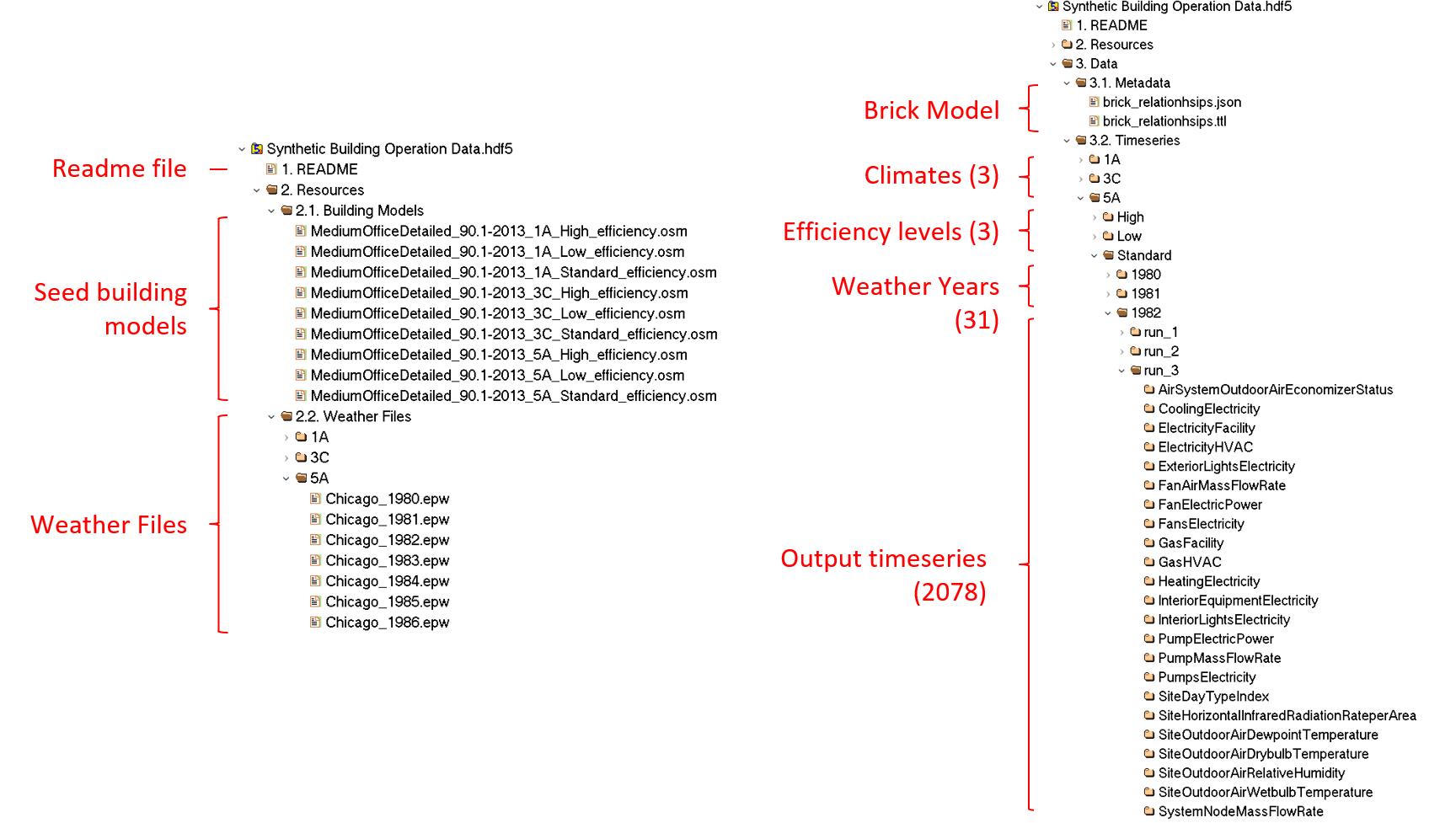

This Jupyter notebook contains Python scripts, dependencies, functions to extract and explore the dataset. The structure of the file is shown in the figure below.

A Brick model of the building could be downloaded here.

A Brick model of the building could be downloaded here.

Generate new dataset:

High-level flow diagram could be found in the Methods section in the paper. For details and source code of generating new dataset, please refer to the README.

Example use cases:

The developed dataset can be used for a wide array of applications. Here, we illustrated two use cases of the large-scale high-resolution data we generated: benchmarking and data-driven building control.

Building Performance Benchmarking

The generated energy consumption and indoor environmental quality data can be used to benchmark various envelope, control and advanced building technologies, especially for areas where real measurement data is not available or inadequate. For instance, even though BPD is the largest database of measured building energy performance in the United States, the sample size of buildings in Miami is 136, which might be too small for robust benchmarking. In this case, the simulation data we generated can be a valuable complementary. The dataset provides system-level end uses and their load profiles for fine granular benchmarking, which are often hard to get from measured datasets. The temporal characteristics - high-load start time, end time, duration, and peak-to-base ratio, could be extracted from the synthetic load profiles and used to benchmark the real building load profiles.

Data-driven Building Control

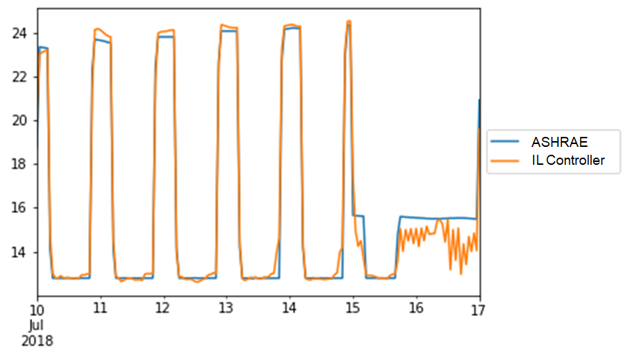

Conventional control techniques, such as PID control, are unable to adapt to the changing building dynamics (due to different occupant behaviors, and building retrofits etc.), to balance the trade-off between multiple objectives (e.g., comfort, energy, costs, and carbon emission), and to respond to the demand signal efficiently. With the rapid development of machine learning (ML) algorithms and computational power, data-driven control becomes a promising alternative for building control. Data-driven control learns the control law, a mapping from the current states (s) to control actions (a) π_(a|s), directly from the building operational data. However, to train a robust, reliable and effective controller, high-quality data is a prerequisite. There are two reasons that it is challenging, if not impossible, to generate those data from building operations. First, the dataset needs to be huge, which requires buildings to operate for years. Second, the dataset needs to explore the state-action space as much as possible, so that the controller would not be stuck in the local optimal. Unfortunately, the existing operational data are likely to be generated from Rule Based Control (RBC), following a given set of rules. Therefore the real operational data usually locates in a limited portion of the state-action space. In this regard, the building operational data generated from simulation could be more valuable for data-driven building control for two reasons. First, it is cheap and fast to generate a huge amount of data through simulation to consider different building operation conditions and disturbances such as weather, occupancy, and etc. Second, and more importantly, different control logics could be tried through simulation without worrying about compromising the indoor environment. In real building practice, building operators are unwilling to try different control logics due to the risks of poor indoor environments. This concern does not exist in a simulation environment. Therefore, the controller could test different control laws to find the optimal one. We introduced a concrete example of how the simulation data can be used to train a data-driven controller through imitation learning. The whole point of training a controller is to learn the mapping relation from states to actions, π_(a|s). There is a whole branch of machine learning algorithms on this topic - Reinforcement Learning (RL). Imitation Learning (IL) is one algorithm of RL. The key idea of IL is instead of trying different control laws and finding the best one, why not imitate the behavior of an expert controller. We applied IL to train a purely data-driven controller using the simulation dataset we generated through the following three steps. First, we identified the ASHRAE Guideline 36, the cutting-edge HVAC control sequence used by the industry, as the expert to follow. Then, we implemented ASHRAE Guideline 36 in EnergyPlus and used it to generate building operational data (a subset of the developed dataset) under different ambient environments and disturbances. Third, we trained our controller to clone the behavior of ASHRAE Guideline 36, i.e., what the output of the expert (action) is given a specific situation (states). This is a typical supervised learning task. We compared the actions suggested by ASHRAE Guideline 36 and those suggested by the IL controller of a typical summer week. As shown in the figure below, these two controllers have similar behaviors.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Assistant Secretary for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Building Technologies Office, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The authors thank Harry Bergmann and Amir Roth of the Building Technologies Office for their generous support. The authors also thank Michael Rossol of NREL for loading the dataset to the Open Energy Data Initiative (OEDI) data lake.

Additional Information

Han Li led the simulations and development of the dataset as well as wrote the manuscript. Tianzhen Hong supervised the research effort, designed the simulations and architecture of the dataset, as well as edited the manuscript. Zhe Wang co-wrote the manuscript and provided support for the simulations. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Tianzhen Hong or Han Li.

Disclaimers

To the extent possible under law, this site has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to AlphaBuilding-SyntheticDataset under the CC BY terms. This work is published from: United States.